New(er) Patterns in (Scientific) Python#

Author: Nathaniel Starkman (MIT, starkman@mit.edu)

This isn’t a tutorial on Python, but this is also a time of exciting change in the Python ecosystem and you might not be familiar with some (relatively) recent developments.

Setup#

If you have an isolated Python you’d like to work in that’s fine. If not, here’s how to set up a uv environment, install dependencies, and connect the environment to your Jupyter.

Install

uv@ https://docs.astral.sh/uv/#installationSet it up

uv sync

[ ]:

Type Annotations#

Type annotations provide information about your functions.

They are useful for:

Understanding a function

Static analysis of that function

Hooking into IDEs

Catching errors

compilation of your Python for speed! See mypyc, codon, nuitka

[1]:

def func(x: int) -> int:

return x + 1

Type annotations are now important in many places in Python. For example…

[ ]:

The Dataclass#

Source modified from https://docs.python.org/3/library/dataclasses.html

[2]:

from dataclasses import dataclass, KW_ONLY, field

import astropy.units as u

When should you use a dataclass? Pretty much any time you have a class that is defined by it’s attributes.

For example…

[3]:

@dataclass

class StarCluster:

"""Class for average properties of a star cluster."""

num_stars: int

radius: u.Quantity

velocity_dispersion: u.Quantity

age: u.Quantity

_: KW_ONLY

name: str | None = field(

default=None, # name is optional, default to None

compare=False, # don't use `name` in `__eq__` checks

hash=False # don't use `name` in hash calculations

)

@property

def number_density(self):

return self.num_stars / (4/3 * 3.14159 * self.radius**3)

Dataclass takes care of generating all the special methods: __init__, __repr__, __eq__, etc.

[4]:

StarCluster?

Init signature:

StarCluster(

num_stars: int,

radius: astropy.units.quantity.Quantity,

velocity_dispersion: astropy.units.quantity.Quantity,

age: astropy.units.quantity.Quantity,

*,

name: str | None = None,

) -> None

Docstring: Class for average properties of a star cluster.

Type: type

Subclasses:

[5]:

StarCluster.__repr__?

Signature: StarCluster.__repr__(self)

Docstring: Return repr(self).

File: Dynamically generated function. No source code available.

Type: function

[6]:

StarCluster.__eq__?

Signature: StarCluster.__eq__(self, other)

Docstring: Return self==value.

File: Dynamically generated function. No source code available.

Type: function

[7]:

pal5 = StarCluster(

num_stars=500,

radius=u.Quantity(100, "pc"),

velocity_dispersion=u.Quantity(5, "km/s"),

age=u.Quantity(12, "Gyr"), name="Palomar 5"

)

pal5

[7]:

StarCluster(num_stars=500, radius=<Quantity 100. pc>, velocity_dispersion=<Quantity 5. km / s>, age=<Quantity 12. Gyr>, name='Palomar 5')

[8]:

pal5.number_density

[8]:

[9]:

tuc47 = StarCluster(1000, u.Quantity(50, "pc"), u.Quantity(3, "km/s"), u.Quantity(10, "Gyr"), name="Tucana 47")

[10]:

tuc47 == pal5

[10]:

False

Besides convenience, dataclasses offer a few advantages:

Consistently structured. This means that tools can easily understand and manipulate dataclasses. We don’t need bespoke tooling.

Statically defined.

Easily introspected.

[11]:

from dataclasses import asdict, replace, fields

[12]:

fields(pal5)

[12]:

(Field(name='num_stars',type=<class 'int'>,default=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,default_factory=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,init=True,repr=True,hash=None,compare=True,metadata=mappingproxy({}),kw_only=False,_field_type=_FIELD),

Field(name='radius',type=<class 'astropy.units.quantity.Quantity'>,default=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,default_factory=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,init=True,repr=True,hash=None,compare=True,metadata=mappingproxy({}),kw_only=False,_field_type=_FIELD),

Field(name='velocity_dispersion',type=<class 'astropy.units.quantity.Quantity'>,default=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,default_factory=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,init=True,repr=True,hash=None,compare=True,metadata=mappingproxy({}),kw_only=False,_field_type=_FIELD),

Field(name='age',type=<class 'astropy.units.quantity.Quantity'>,default=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,default_factory=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,init=True,repr=True,hash=None,compare=True,metadata=mappingproxy({}),kw_only=False,_field_type=_FIELD),

Field(name='name',type=str | None,default=None,default_factory=<dataclasses._MISSING_TYPE object at 0x1015ccce0>,init=True,repr=True,hash=False,compare=False,metadata=mappingproxy({}),kw_only=True,_field_type=_FIELD))

[13]:

# With asdict, we can convert the dataclass to a dictionary!

asdict(pal5)

[13]:

{'num_stars': 500,

'radius': <Quantity 100. pc>,

'velocity_dispersion': <Quantity 5. km / s>,

'age': <Quantity 12. Gyr>,

'name': 'Palomar 5'}

[14]:

# With replace, we can create a new instance of the dataclass with ANY fields

# changed! Here, we change the number of stars to 100,000.

replace(pal5, num_stars=int(1e5))

[14]:

StarCluster(num_stars=100000, radius=<Quantity 100. pc>, velocity_dispersion=<Quantity 5. km / s>, age=<Quantity 12. Gyr>, name='Palomar 5')

[15]:

# Quick test of equality under replacement

pal5 == replace(pal5), pal5 == replace(pal5, num_stars=1_000)

[15]:

(True, False)

[ ]:

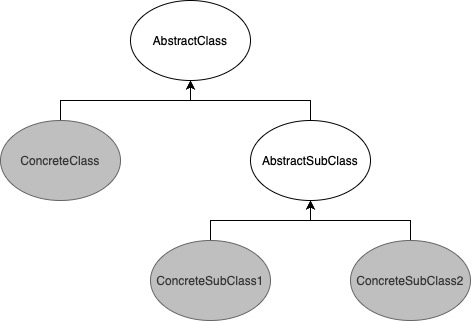

Abstract/Final Pattern#

Adapted from https://docs.kidger.site/equinox/

This is a pattern that is mandatory in Julia and has been emerging in popularity in the ML community in Python.

It produces VERY clean and readable code and has easy to understand class inheritances.

Every class must be either:

abstract (it can be subclassed, but not instantiated); or

final (it can be instantiated, but not subclassed).

[16]:

from abc import ABCMeta, abstractmethod

from typing import final

[17]:

# This class is abstract and cannot be instantiated

class AbstractClass(metaclass=ABCMeta):

"""Abstract base class."""

@abstractmethod

def method(self):

pass

[18]:

# This class is concrete and can be instantiated

@final

class ConcreteClass(AbstractClass):

"""A concrete subclass of AbstractClass."""

def method(self):

return "Beautiful is better than ugly."

[19]:

# This class is abstract and cannot be instantiated.

# But it's subclasses are concrete and can be instantiated.

class AbstractSubClass(AbstractClass):

"""An abstract subclass of AbstractClass."""

@abstractmethod

def another_method(self):

pass

@final

class ConcreteSubClass1(AbstractSubClass):

"""A concrete subclass of AbstractSubClass."""

def method(self):

return "Explicit is better than implicit."

def another_method(self):

return "Simple is better than complex."

@final

class ConcreteSubClass2(AbstractSubClass):

"""Another concrete subclass of AbstractSubClass."""

def method(self):

return "Complex is better than complicated."

def another_method(self):

return "Flat is better than nested."

[20]:

ConcreteSubClass1().another_method()

[20]:

'Simple is better than complex.'

[ ]:

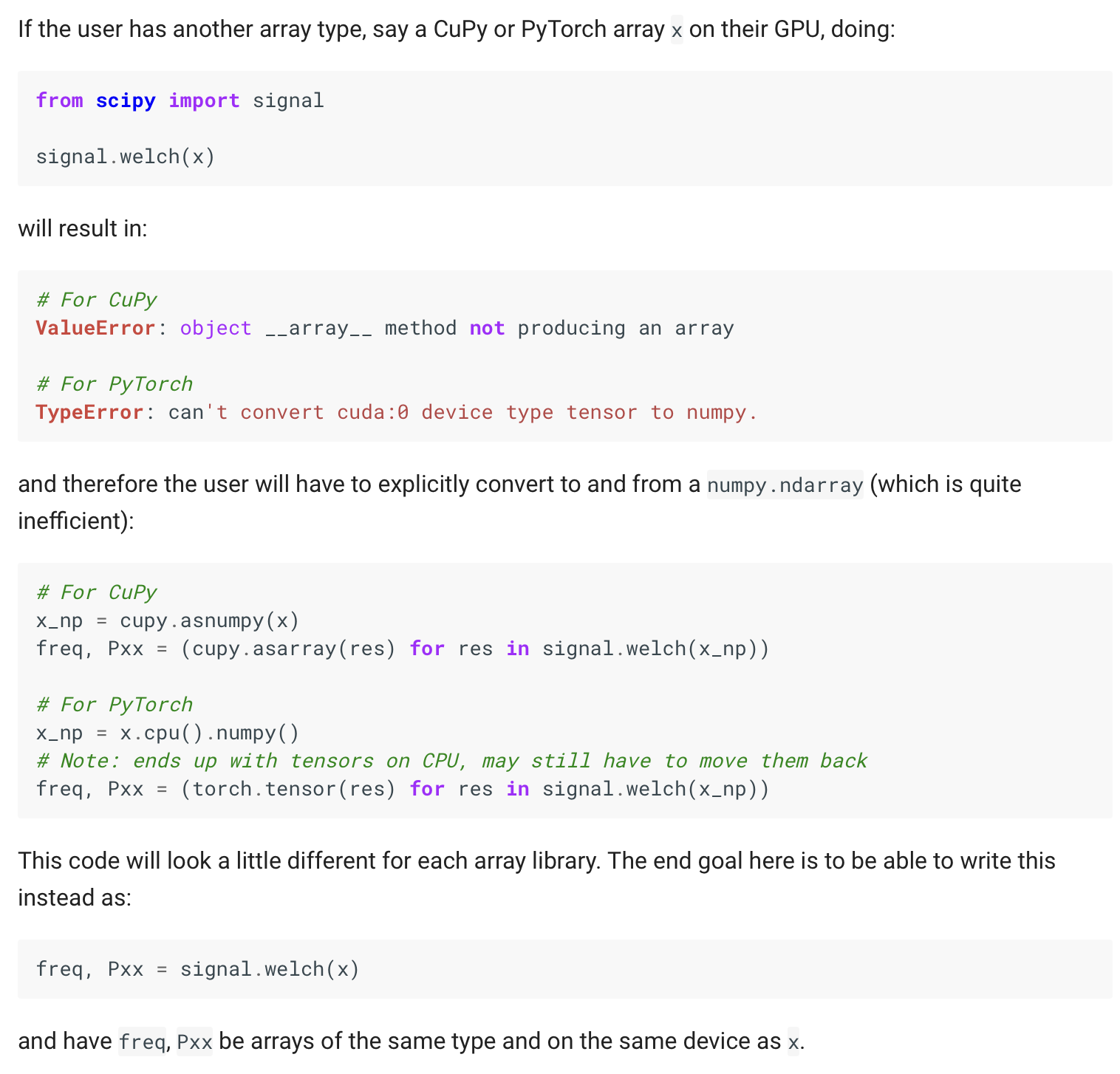

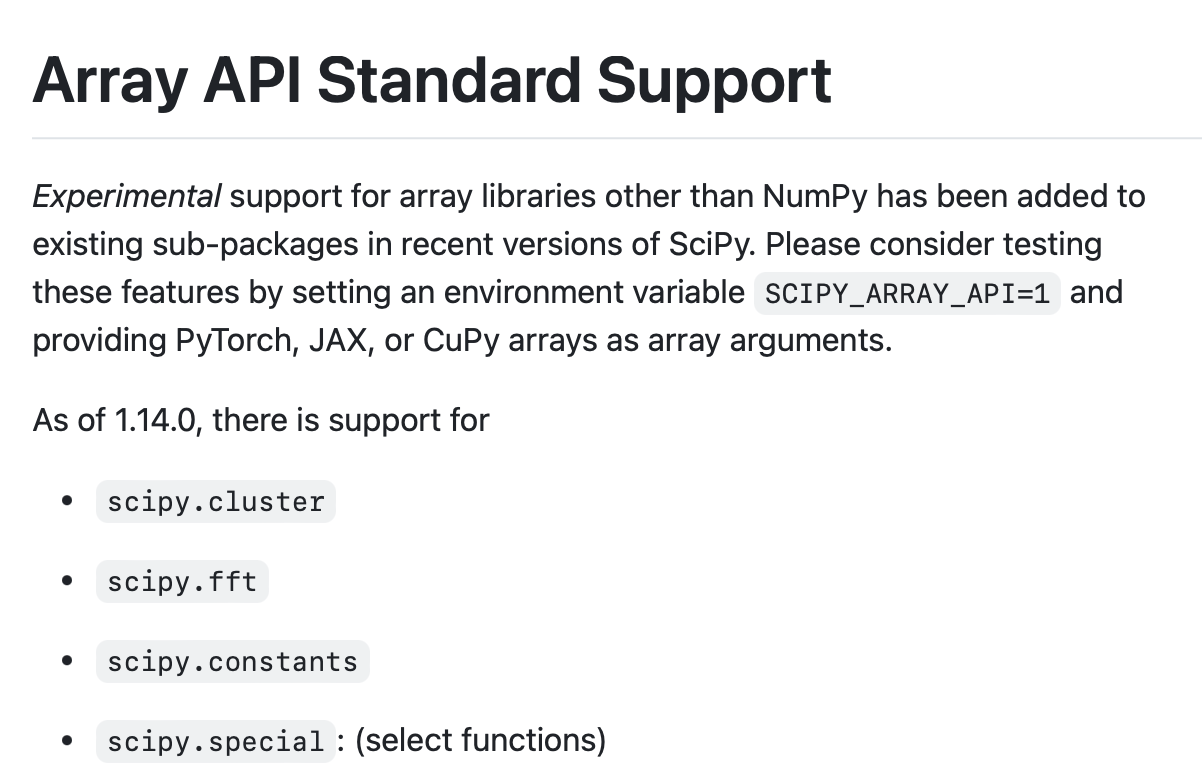

Array API#

See https://data-apis.org/array-api/

There’s a lot to say about the Array API.

Here’s two:

It’s unifying the numerical Python API

It enables a lot of interoperability

Unifying the API does mean some function names are changing!

[21]:

import numpy as np

np.concat

[21]:

<function concatenate at 0x108007d70>

[ ]:

Recap#

Type Annotations

Dataclasses

Abstract / Final

Array API

[ ]: